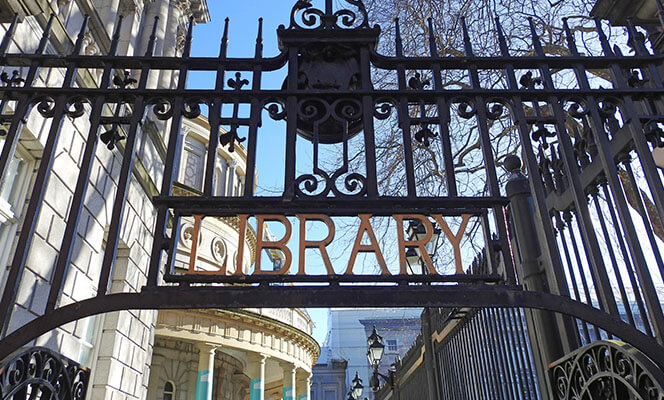

It’s still early in the morning when I walk up the steps to the National Library.

Standing on the porch, through the fence I can see TDs totter up the path next door, folders underarm, heading into the Government buildings. This Kildare Street building has housed Dublin’s main public reference library since 1890. In Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, he even describes students gathering here to smoke and chat.

The very first time I ever came in here, I got as far as the hall.

Inside, it is quieter than even a library should be. Although, there are a few eager types waiting in the lobby. A cleaner polishes around the bronze bust of Senator Michael Yeats, son of W.B., and smiles at me pacing the floor.

I’m due to meet with Katherine McSharry who is Acting Director here. She’s been with the National Library since 2007. Despite the fact that around 300,000 visitors cross the threshold every year, I want to ask her why it can feel like an intimidating place, only to be entered with a strict purpose and a serious face.

Welcoming new faces to the National Library

Katherine, for her part, understands where I’m coming from. “I remember the very first time I ever came in here,” she says. “I got as far as the hall.”

She continues: “There was an exhibition on in the hall. There was another bit of it that was up the stairs and I just wasn’t sure if I was allowed go up – and I went away. I always remember it. And I’m always glad I had that experience, because it’s very easy to forget what it’s like for someone to come in for the first time when you get used to a place.”

Until quite recently, visitors tended to be people who came here when they had research to do. It’s only in more recent years that there are facilities for people who just want to see some of the collections or an exhibition.

Katherine especially enjoys events, like history lectures and poetry readings, that attract people who wouldn’t usually come in. “So you come in and get the sense of: ‘Oh, this beautiful space is lively and exciting. There’s something here for me’,” she says.

What’s in the collection?

As with all cultural spaces, the work of libraries has expanded and its new facilities are opening it up to a wider audience. However, the base of its offering is the collection that it has been building up since it first opened over 130 years ago.

“We have every newspaper published in Ireland as far back as they go – right up to the day before yesterday,” says Katherine. “All the regional papers as well.”

People are always drawn to their local papers. They can hope to find a mention of their grandad winning a club medal.

There’s a point in family history where if you go far enough back, something bad is exciting.

The National Library also collects all the books published in Ireland every year. There are even bundles of brightly coloured Marian Keyes’ somewhere in the dusty stacks.

“That doesn’t seem like a huge deal but, in 50 years time when certain paperbacks are out of print, this may be the only place where you can get them,” explains Katherine.

Katherine McSharry

Since 2011, the National Library also collects websites. It acts as the digital memory of Ireland and is like an internet version of ‘Reeling in the Years’.

The team here identifies moments that are a “big deal for Ireland”, such as the Marriage Equality referendum and the 1916 centenary. Then it collects websites, even satirical ones, that reflect the spectrum of opinion on these events.

There are drop-in genealogy facilities too. Here, the National Library’s specialists will help you find that rogue ancestral serial killer.

“There’s a point in family history where if you go far enough back, something bad is exciting,” Katherine laughs. The library also hosts children’s workshops with storytelling and trails through the buildings.

Visitor-friendly plans for the library

And big changes are afoot at the library too; a huge renovation project to open up the space is currently underway.

“What you notice when you come in off Kildare Street, a big imposing street, and through this quite narrow doorway is that everything looks very Victorian and imposing,” says Katherine.

When you come in, the very first thing you will see is a café and a shop.

“And you’ve got to get through the pillars. And when you walk in through the entrance, people often ask: ‘Am I supposed to be here?'” she says. “What the development will allow us to do is almost re-imagine the library as if we had built it from scratch.”

Book storage is currently located along the busier Kildare Street side and the public facilities are all towards the back. “The redevelopment will allow for the swapping around of those two,” explains Katherine.

Our job is to go to find you and make sure you connect with this.

Simply put, the Victorian-era west wing, which is currently used for storage, will be transformed into a public area with a new entrance. 500,000 books are being moved as part of the redesign, which will cost an estimated €10 million.

“When you come in, the very first thing you will see is a café and a shop,” says Katherine. “The books will be in climate controlled storage at the back.”

Archives that inspire interesting exhibitions

The newly renovated library will also host an exhibition on the work of poet Séamus Heaney. Entitled Seamus Heaney: Listen Now Again, this multisensory experience is currently on show at the Bank of Ireland’s Cultural and Heritage Centre on Westmoreland Street.

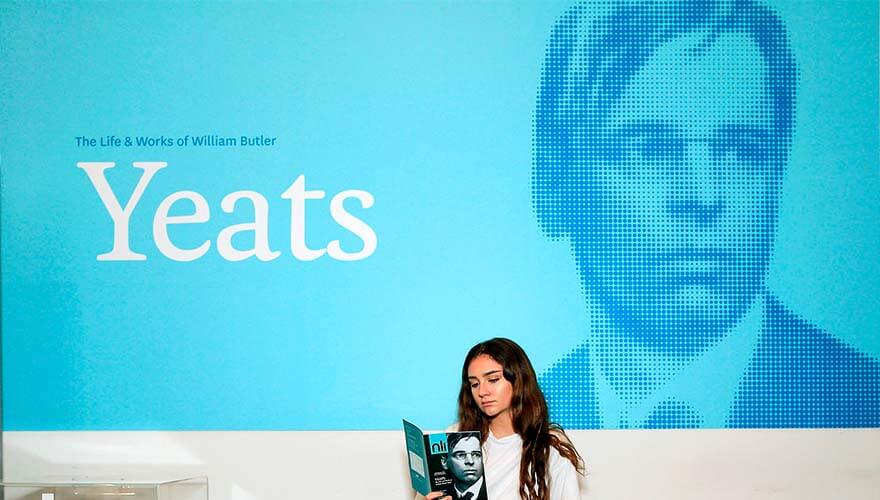

However, it will soon have a permanent home in the attic of the National Library. It will be similar to the W.B. Yeats exhibition housed in the basement since 2006. This was never intended to be permanent, but it is now the library’s biggest draw.

The National Library also houses an extensive archive. “The emotional impact of archives is so far away from that idea of huge amounts of material and wading through it,” says Katherine.

“We had the Scottish Minister for culture in and we were showing her some stuff from James Connolly, who was born in Scotland,” Katherine says. “The letters he wrote to Lily, who went on to be his wife, and the witness statement that Nora, his daughter, wrote after their last visit to see him.

“In it, Lily says to him: ‘Oh, but James your beautiful life’. And he says: ‘Wasn’t it a fine life, Lily? And isn’t it a good end?’”

On the anniversary of historic events in Irish and international history, the library often pulls together its most interesting archive content for temporary exhibitions.

Past themes include the Dublin Lockout of 1913 and World War I. As well as photos and newspaper clippings, the likes of letters and diary entries are also put on show.

The National Library is always searching for new ways to bring Dubliners in. “It’s not our job to sit here and say we have these marvellous things and be delighted with ourselves,” says Katherine. “Our job is to go to find you and make sure you connect with this.”

Step back in time at The Reading Room

Katherine takes me up the stairs, past stained glass windows and the genealogy room. There, some older men – maybe retired – are already clicking and scrolling through the screens, taking delight in uncovering branches of the family tree.

We soon arrive in the Reading Room. Under the turquoise dome, the rows of green glass lamps give off that pleasing scholarly Good Will Hunting feeling. Katherine tells me about a library frequenter, Father Dineen, who wrote dictionaries and had a special seat where he’d work and eat oranges all day.

He’d be furious if someone would come in who didn’t know it was his desk.

“He’d be furious if someone would come in who didn’t know it was his desk,” she says. “They would innocently sit at it and he’d be giving them really angry eyes.”

W.B. Yeats worked here too and James Joyce even set the ninth episode of Ulysses in the National Library of Ireland, straying from his usual form by using people’s real names.

Visiting the National Library

Downstairs at the W.B. Yeats exhibit, an older woman sits in a booth with her head against the wall, listening to a documentary about Yeats and his many ancillary loves.

In another section, pictures of the isle of Inisfree at sunset flash pink on a screen and then fade. The voice of Sinéad O’Connor recites: “a terrible beauty is born”.

Books in glass cases sit open at pages where Yeats wrote drafts of poems and plays. There are letters and postcards, as well as pictures of him in various states of dapper. His later portraits are more relaxed with dogs by his side, shirt collar open and hair slightly askew.

There is no sense of the traffic outside or the government squabbles next door in this book-lined cocoon in the heart of the city.

Go to the Library’s website to plan a visit or check out Dublin’s other museums.