We all know Grand Canal as the home of Google but unbeknownst to many, tucked among the tech giants is a building where ancient crafts are still practised, The Design Tower.

The Tower’s seven stories of studios play host to jewellers, fashion designers, conservationists and more.

The Tower started its life as a sugar refinery in 1862. In 1978 the IDA bought the Tower to form part of their Enterprise Centre with the aim of preserving and restoring it to create a home for many of Dublin’s craftspeople. Today this enterprise is managed by Trinity College. Dublin.ie is going behind the tower walls and meeting its residents to see what it’s like to work in a hive of creative activity. Here, Amy Sergison meets Michiel DeHoog, a violinmaker who has been working in the Design Tower for twenty years.

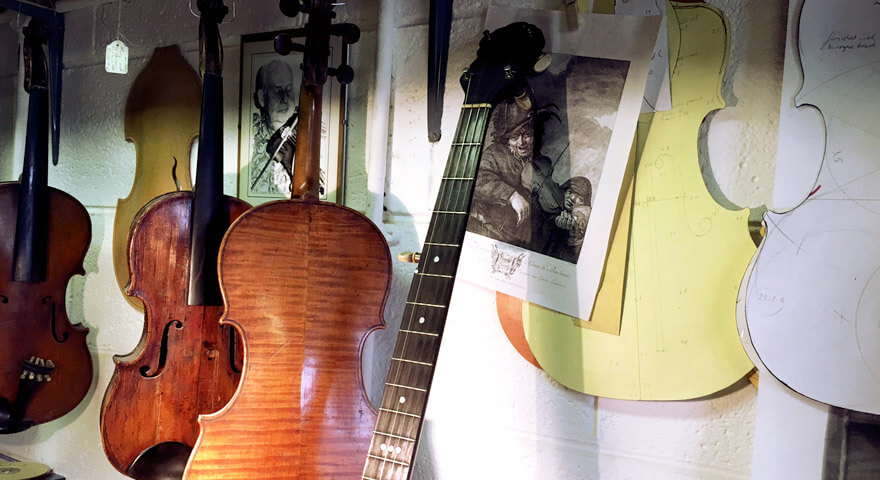

I have been a violinmaker for 40 years. I make violins, violas and cellos, the instruments for a string quartet. I also look after people’s instruments; sound adjustments, restorations and things like that.

I was working in Paris before I came to Ireland. I was looking for a workspace where I could share with other craftspeople. Here, I found exactly what I was looking for, a place where you can work but aren’t isolated. I’ve been here twenty years now and it’s worked out really well.

The Design Tower is a very pleasant place to work. It’s very stress free. We share common spaces where we can have a chat or sometimes help each other. I can solve woodworking problems for a jeweller and a jeweller could help me with some silverwork. It’s a really healthy sharing community, how it used to be in the past when trades would always work together. I cannot praise the sense of community highly enough.

Violinmaking is a very old craft that has been handed down through the ages. We do it in the same way that it was done in the 1500s when the violin was born, but it is very much linked to modern times. We hear music on our radios and our laptops every day. Classical music is like a colour in a room. If you really start listening to the sounds of the instruments and how they are played, it has many, many layers, all there to be discovered like the pages of a book.

My work is handmade from maple and spruce. The wood comes from very special forests that grow the kind of wood that violinmakers like. We all have our own tastes. We are all looking for very beautiful wood but also wood that has good tone. That is hard to find. You spend a lot of time, particularly at the beginning of your career looking for the right kind of wood and building a stock of it.

It takes a long time to make a violin, about 150 working hours, a cello at least double that. With bits and pieces of work in between I never make more than five or six instruments a year, which is great because you can concentrate on each instrument. All violinmakers want to do is make something really beautiful that sounds exquisite.

When you make an instrument you are obviously trying to do your best. You always think ‘ this is going to be my masterpiece’. If you don’t think like that then I don’t think you should be doing it, you have to give it your all.

When you’re making an instrument you are hoping for this amazing thing and you might be very happy with the result but as soon as your start on the next instrument you start to think about things you would change. You have to remain critical or else you wouldn’t evolve and you would be making the same thing for fifty years, which would be really boring.

For more information on the Design Tower visit www.thedesigntower.com.