The last Typewriter Shop in Dublin

On Dorset Street in Dublin’s north inner city, there’s a typewriter shop that’s been there as long as I can remember.

Founded in 1983, it’s run by Joe Millar and his son, who’s also named Joe. It’s the last typewriter shop in Dublin and the only one in the Golden Pages where it’s listed, simply, as ‘The Typewriter Shop’.

A million machines, but no more manufacturers

Before setting up the shop, Joe Sr. had worked in the typewriter trade for the American manufacturer Remington.

“They had offices in Dublin, Belfast, Cork, Galway and Limerick,” he says. They sold typewriters to offices and serviced the machines to keep them in working order.

“There were a lot of typewriter dealers then,” he says. “There were about ten dealers in Dublin and there would have been about ten manufacturers – maybe more”.

The manufacturers assembled the typewriters, which were made elsewhere, for the Irish market. Every office had at least one typewriter and most had many more.

Millions of typewriters were made and there are no manufacturers left.

Remington built the first commercially successful typewriter in 1873. A group of inventors, which included Christopher Latham Sholes and Carlos Glidden, designed it using an earlier prototype for inspiration. It was known as the Sholes and Glidden typewriter – or the Remington No. 1.

“There were other brands and machines as well,” Joe Sr. tells me. “Underwood would be the other American brand of machine. And there were other brands that just lasted a short amount of time and disappeared – or the patents were bought by other manufacturers and redesigned.

“So it’s strange to say that millions of typewriters were made in the world and there are no manufacturers left.”

The tricky trade of typewriter repairs

The move to computers wiped typewriters out. However, some are still used – not just by individuals, but by offices too. When something goes wrong with the machine, it needs to go to the shop to be fixed.

One typewriter in the shop on Dorset Street has 3,500 moving parts and there could potentially be a problem with any one of them.

As I stand in the shop talking to Joe Sr. and Jr., the doorbell goes and a man delivers an electronic typewriter to be fixed. Joe Jr. deals with newer models, which are mostly electric, while Joe Sr. deals with the older, mechanical machines.

A Bar-Lock typewriter manufactured in the late 1800s

Although electric typewriters were around since the early 20th century, it wasn’t until the 1960s that they became popular and relatively affordable – first for offices, then for consumers at home.

The IBM Selectric, which used a spherical, spinning ‘golf-ball’ element to imprint text on paper was, in Joe Jr.’s words, “the Rolls Royce of machines”. It sold to offices for a hefty £1,200.

“Now, because there’s no typewriters manufactured anymore, any company that still has a typewriter finds it hard to get parts,” says Joe Sr. “Sometimes we have to circumvent and try to make something up. With the mechanical machines it’s not too bad, but with electronic machines it’s chaos, because parts are just not available.”

They’re all nice to look at. Until they break.

They deal with this by finding other machines to “cannibalise” – taking parts from one typewriter to repair another. How many days does it take to repair a typewriter, I ask. “We never give an answer to that,” Joe Sr. says. “It depends on what’s wrong with it.”

When they have no other option, they manufacture their own parts in different ways. “You can get a part welded. Build up a part that’s been worn.” For electric typewriters, they do minor circuit board repairs. However, for major repairs, like burnt-out boards, they send it to someone in Wicklow.

A tour of The Typewriter Shop’s treasure trove

Joe Sr. starts to show me a couple of the typewriters sitting on the shelves and tables of the shop.

One, a Bar-Lock typewriter manufactured around 1894, has separate keyboards for lowercase and uppercase letters, as well as an elaborate curving copper plate above the keyboard bearing the name of the manufacturer.

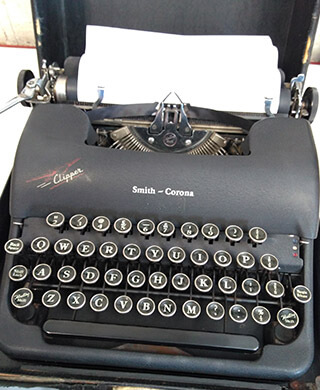

A portable Smith Corona typewriter

It’s in full working order, so Joe Sr. punches the keys. It sounds like gunfire.

Then he places an Olympia typewriter from around 1970 on the table. Joe Sr. calls it “a machine with a bit of character”.

It’s out of its plastic casing and I can see the complexity of its internal mechanism: skeletal metal rods join keys to the typebars.

Another typewriter is fished from the shelf – a matt black Smith Corona portable. “That’s lovely,” I say. “They’re all nice to look at,” Joe Jr. says. “Until they break”.

A counterpoint to our throwaway culture

Then, we start talking about other shops – many of which have disappeared from the city. “The trades have vanished in Dublin,” Joe Sr. says.

He tells a story about a pair of shoes that he had for years. When he tried to get them fixed, the manufacturer told him he was better off getting rid of them and buying a new pair.

“It’s a throwaway society,” he says. Yet, that’s certainly not the case here, where, thanks to a bit of love and care, 120-year-old typewriters still work like they did the day they were built.

Visiting The Typewriter Shop

For typewriter repairs or to purchase a new old typewriter, visit the Typewriter Shop on Dorset Street.

It’s just a ten minute walk north of O’Connell Street, past The Rotunda, just beyond Parnell Square. It opens every weekday until 5pm.

To find out more, visit the store’s website but it’s well worth a visit in person.